The Loom of Becoming

In the forests of Europe, women still spin. Beside baskets of wool and plant-dyed cloths, fingers twine in the candlelight as dusk falls. These quiet acts of resistance are pushing back against the technofeudal hegemony we live in, offering a glimpse of what is still real.

The spindle, distaff and loom have always shaped the fabric of life, and with it, past, present and future. Women have sat with flax and fleece to clothe the body and spin spells since the beginning of time.

Across cultures, women are the masters of weft and warp. In Ireland, Bridgid was the first weaver, her white threads laid on the loom to heal and bless. At Imbolc, women still put their fabrics out under the stars to absorb her blessing. In Welsh tradition, writing a poem is to weave a song and in Sanskrit sutras are threads. In ancient birth rituals across Europe, midwives have tied threads around newborns as protective charms, and spun them garments that could not be pierced by sword.

These women understood something that we have mostly forgotten: that spinning calls world into being.

The symbol of the thread and spindle belongs to the Fates. In Norse tradition, the Norns spin, measure, and cut the threads of life. They draw near when a woman prepares to give birth to twist the golden thread that binds fate to the child’s breath.

In the Slavic tradition they are Laimas, measuring the thread of a child’s life over the cradle. In Greece they are the Moirai, and in Rome the Parcae. All fate-spinners are female trinities.

The instrument they use for spinning, the stick-like distaff, is also a wand of fate. In the Norse tradition, the Völva, the seeress, uses the staff to access her Inner Sight. With it, she spins wyrd – what must be. The distaff represents her craft and authority, and with it she prophecises, determines fate, guides the dead, and heals the sick. Her distaff is the axis between worlds. From her flax, the fates of humans are teased out and twisted into form. The modern word “weird” has its roots in this wyrd: the force of becoming.

The web of wyrd spirals, coils, loops, knots, and is always in the process of becoming. In the megalithic temples (womb tombs) scattered across the European continent, triple spirals can be found carved deep into the rock. The time they represent is is not linear; it is layered, spiralling, and threefold. The carvings are not abstract motifs, but cosmological diagrams: maps of time.

The archetypal manifestations of the triple goddess: Maiden, Mother, Crone, are not just phases of womanhood. They represent cosmological anchors in a world that understands time as recurring, generative, and cumulative. And the triple spiral links them through geometry, myth, and embodied patterns.

In these megalithic structures, the dead were placed in chambers shaped like uteruses to be reborn. Here, time contracts and expands in recurring cycles, just as it does in myth, orgasm, and birth. In the darkness the dead return to the Great Mother, where they are spun back into life.

The double helix of our DNA spins life into being, nautilus shells unfurl in sequence, galaxies turn like dervishes. Even quarks whirl into matter.

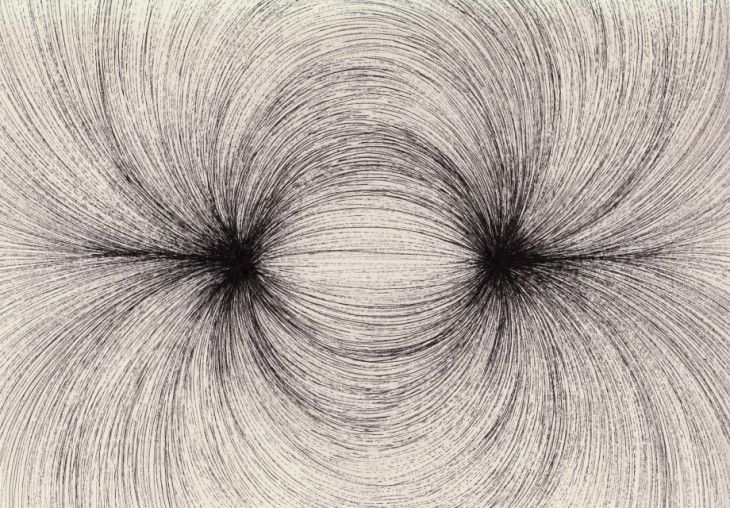

If we imagine the fabric of reality not as fixed and flat, but more as soft, curved, and woven, it becomes a shimmering net of potential stretched across existence. When something, or someone, with a permanent centre of gravity enters the field – whether a planet, force, or human presence – it can bend the weave and pull the warp.

This is not just a metaphor, but mythic cosmology – a way of seeing that reveals the structure of reality in the language of images, story, and embodied cyclicality. In modern physics, spacetime is not a void; it is responsive, pliable, and curved. What we perceive as gravity can be described as a dip in the cosmic fabric, the bowing of space and time around mass.

When physicists describe this curvature, they speak of the same field of becoming that the Völva senses with her staff.

Now imagine that the distaff of the völva, the priestess-weaver, is not simply a stick for spinning flax, but a staff that senses these tensions – the pull between what is and what is becoming. She feels where the thread is thinning, where it loops and gathers, and where an opening in the weave is possible.

Shortcuts between corners of space and time are like folds of simultaneity: wormholes in scientific jargon. Such kinks in the fabric of timespace are where your great-grandmother enters your dreams to convey a message.

The ancients knew that the fabric of the weave could open – that there were sacred times, places, and states of being where the veils were gossamer thin, and the past drifted into the present, so that the future could be discerned. A woman at her spindle might catch a glimpse of wyrd.

Human fate is not fixed; it is woven, and can therefore be rewoven. It is in these transcendent states that we can heal the past and prepare the future.

In other words, meaning can bend reality. A birth, a death, an great shock, or a moment of three-centred presence (unity of body, emotions and intellect), can create a window in the weave. This is from where miracles originate.

What the physicist calls distortion, a seeress might call a portal.

Myths of spindles, turning wheels, and celestial churning are not mere allegories, but descriptions of ancient experiences of the cosmic order and potential for transformation. They are beacons from a time when humans lived in resonance with cosmic cycles.

In Hindu cosmology, gods churn the Milky Ocean to extract amrita, the nectar of immortality. The churning unfolds between two fundamental cosmic forces: serpent and mountain. The serpent is a symbol of dynamic energy and cyclical time, the mountain represents the still axis around which the stars revolve. Together they mirror the spindle and thread spinning creation into being.

The Milky Ocean is the Milky Way, and the churning motion reflects the precession of the equinoxes – the slow, 26,000-year wobble of Earth’s axis, which causes the celestial pole and zodiac signs to shift over millennia. Ancient sky-watchers saw this vast spiral in the heavens and encoded it in myth.

Because of the phenomenon of precession, the stars “drift” slowly in relation to the seasons. Over long periods, the constellations shift out of alignment with the ancient temples, calendars, and cosmological myths that indicated our position in the cosmos. In mythology, this lost alignment between heaven and earth is symbolised as the broken cosmic axis.

It reminds us that we are no longer aligned with the heavens the way our ancestors once were. The wisdom of alignment – living in rhythm with the stars, the earth, spiralling time – has been forgotten or distorted, and mankind has fallen.

Even language remembers. The Latin verto, the Saxon weorthan, the Norse verða, the German werden: all mean to turn, to become. In many of these tongues, the verb for turning also became the verb to be.

To take up the spindle today is to reclaim the axis of becoming and to re-enter the spiraling world of eternal recurrence. Craft once meant knowledge, healing, power. It still does.

Welcome to the Skeleton Key.

Do you have a question for The Skeleton Key?

Leave a comment