I come from the left. My values were shaped there: solidarity, justice, compassion for the vulnerable, resistance to power structures. These aren’t abstractions; they are the ground I stand on. And because I care about these values, I can’t ignore what’s happening in the political and cultural left today.

The left I once knew spoke for dockworkers, immigrants, single mothers, the homeless – those with little agency who needed the status quo to change. In much of the West, that’s no longer the case. Left-leaning ideas dominate universities, media, the arts, and even corporate branding.

Yet the story we tell ourselves hasn’t changed. We still cast ourselves as underdogs fighting oppressive powers. That might be comforting, but it is no longer true. We hold significant cultural power while pretending we don’t, and when someone points out the contradiction, our instinct is often to exclude rather than approach diverging views with curiosity.

In Jungian terms, our shadow is the part of ourselves that we can’t or won’t see. It’s the personality traits we project onto others while denying them in ourselves. The shadow of the contemporary left represents the gap between our self-image as righteous resistance, and the reality of acting as cultural gatekeepers, policing orthodoxy and speech.

We talk about “speaking truth to power,” while wielding considerable cultural power ourselves. To reclaim authenticity and do the good we claim to want, what is needed now is shadow work: honest self-reflection about our blind spots.

Shadow work is not about abandoning our values. It’s about taking responsibility for the harm we might cause even when our intentions are good. And it is precisely in the places where emotions run hottest that the shadow tends to flare up most: where complex realities get flattened into simple moral narratives that make us feel good while failing the people we claim to want to protect.

Performative Solidarity

One place this has become glaringly visible is the Palestine–Israel conflict. A war is never a simple struggle of good versus evil. It is a tragedy with deep historical wounds, asymmetries of power, and genuine suffering on all sides. To see that complexity requires maturity, compassion, and the ability to hold more than one thought at once: that Palestinians deserve dignity and safety; that Israelis deserve dignity and safety; and that the violent extremism of some does not define an entire people.

And yet, in much of Western activism, the conflict is treated as a symbolic morality play. Support for Palestinians has become a tribal marker on the left, a way to signal one’s alignment with “the oppressed.” Too often it is performative, reducing a complex, bloody, heart-wrenching conflict to hashtags, slogans and flags.

Many Western activists seem uninterested in listening to Israelis or Palestinians who hold nuanced views which call for mutual recognition and tangible improvements for people on both sides. Instead, activists reward each other for moral certainty and outrage. This may feel righteous, but risks becoming little more than hollow theatre – or worse, harmful to Palestinians.

This dynamic is not unique to Palestine activism. It reflects a deeper habit in leftist spaces: the conflation of performance with action. The urge to demonstrate allegiance to the “right” side can become more important than engaging honestly with messy realities. We see the same patterns elsewhere.

The Cost of Simplification

Consider the current debates around gender identity. Earlier feminist movements fought for women based on material realities: reproductive rights, economic independence, and freedom from male violence. Their analysis was grounded in the recognition that women are oppressed as a sex class, because of their bodies and their reproductive role.

In recent decades, parts of the left have shifted toward viewing reality through the primary lens of identity. Inspired by post-structuralist thinkers like Michel Foucault, the focus has turned to how language and norms construct categories like “man” and “woman.” This offers valuable insights into how power operates. But as with Palestine activism, complexity is flattened. For many activists, and regular left-wing adherents who want to see themselves as modern, tolerant and inclusive, questioning the conflation of sex and gender is treated as heresy. Women who raise concerns about the erosion of single-sex spaces or language around motherhood are accused of bigotry, regardless of their long histories of fighting for women’s rights.

The pattern repeats: a moral hierarchy of oppression places some identities above others; an instinct to punish dissent rather than engage with curiosity; a performative solidarity that ends up harming those it claims to protect.

In this case, women’s material needs are sidelined in favour of identity-based narratives that erase the political significance of sex altogether. Just as with Palestine activism, the shadow here manifests as the left’s discomfort with complexity. It is easier to perform moral purity than to sit with nuance.

Why Shadow Work Matters

What connects these issues is not that they are identical; it is the underlying cognitive approach. The left, understandably wary of power structures, often fails to see the cultural power it holds. That power, when combined with a refusal to face our own contradictions, leads to dogmatism.

We romanticize movements abroad without reckoning with their values. We punish internal dissent without sufficient self-inquiry. We gaslight ourselves with the story that we are always on the right side – the side of the oppressed – even when reality is far messier.

Shadow work means bringing these contradictions into the light. It means being willing to hear uncomfortable truths. It means supporting Palestinians and Israelis as human beings rather than symbols, and accepting people who dress or behave differently without erasing women as a sex class.

I’m calling on the left to grow up – to reclaim the humility and courage that real justice demands. Because the alternative is fragmentation: a politics so polarized and performative that it tears apart the very fabric of society.

We can do better than ceding reality-based conversations to the right. We can be mature enough to hold complexity and compassionate enough to refuse simplistic narratives.

That maturity is what our politics needs now. Shadow work is not an attack on the left; it is an act of love – a willingness to face our own reflection so we can heal, and so our values can mean something again.

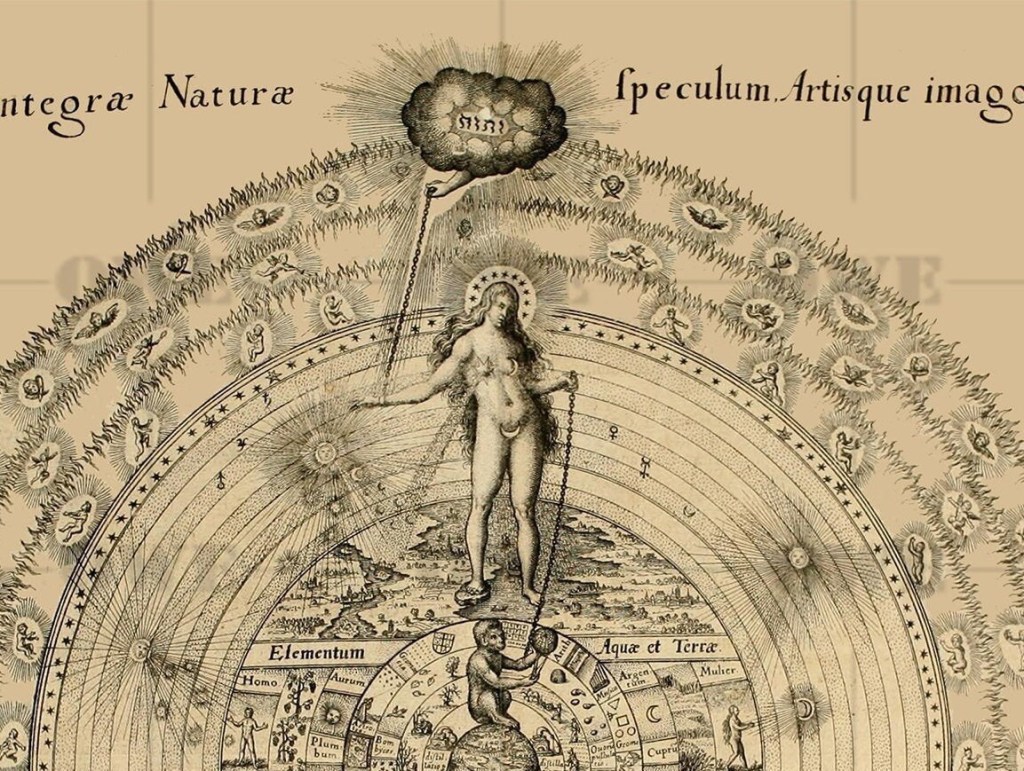

If the contemporary left is struggling, it is because it has forgotten the oldest esoteric principle: as within, so without. Any movement that cannot face its shadow ends up creating the very conditions it claims to oppose (see also previous blogpost The Enneagram: A Living Teaching, Part 1). I name this shadow because I still believe in justice, in equality, in the dignity of the least protected. But those values mean nothing if we can’t bear to face our own reflection.

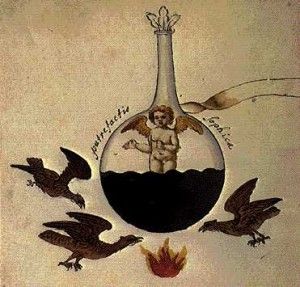

On The Skeleton Key, this work of looking inward is not abstract. It is the same discipline that mystics, alchemists, and initiates have practiced for centuries: the work of seeing what is hidden, dissolving what is false, and allowing a truer form to emerge.

Every tradition of inner transformation begins with the same demand. Stop projecting. Turn the light toward yourself. In political life, the refusal to do this creates movements that cannot tolerate contradiction and individuals who mistake certainty for truth. But when we bring the tools of inner work to our public life, something else becomes possible: clarity without cruelty, conviction without fanaticism, solidarity without performance.

The Skeleton Key is an invitation to that deeper responsibility. If we want a politics capable of justice, we need a self capable of honesty. The descent into our own shadow is not a detour. It is the doorway.

Welcome to The Skeleton Key.

Do you have a question for The Skeleton Key?

Leave a comment